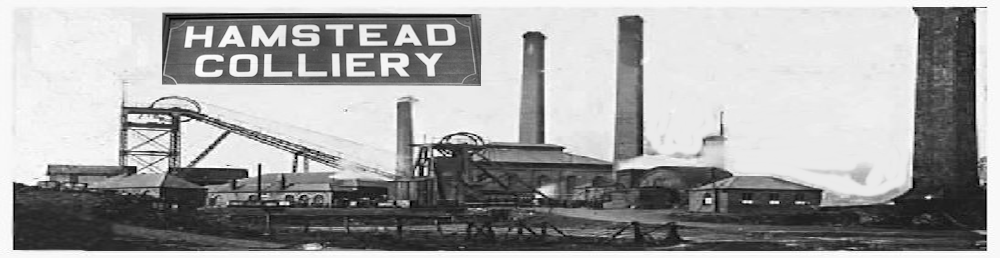

Welcome to the new Hamstead Colliery site - Page Not Found

Hi, sorry but the page you are trying to access cannot be found.

This may be because you are accessing using a saved link or following a Google link that has not yet updated to the new page names.

This new site has different page names so please use the navigation links to find the new version of the page you were looking for or use the search facility.

Go to the Home Page for Hamstead Colliery